The Art of Emptiness

. . . . . . . . .

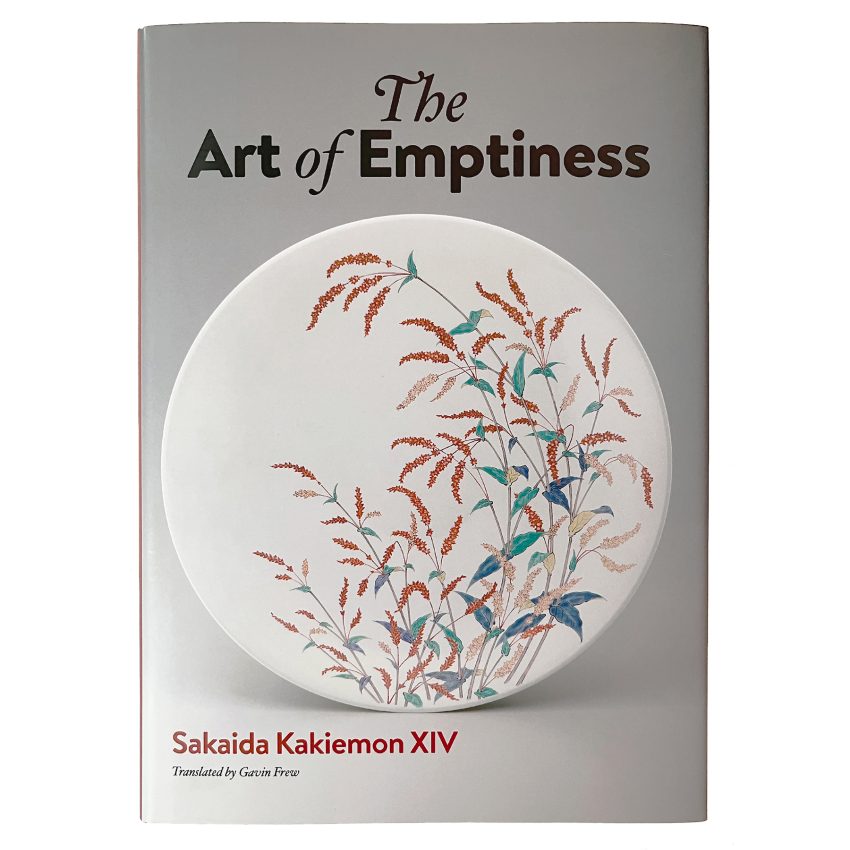

The Art of Emptiness by Sakaida Kakiemon XIV

When it comes to Japanese ceramics, I have always been particularly drawn to the richly textured and expressive stoneware pieces more associated with the tea ceremony. So I must admit that it was not without a little apprehension that I decided to pick up a copy of Sakaida Kakiemon XIV’s book illuminating the sophisticated porcelain ware that he and his forebears (and now his son) have been producing in the Arita area of Japan since the beginning of the Edo period in the early to mid-seventeenth century. What initially attracted me to the book was actually the title “The Art of Emptiness”, the specific aesthetic that epitomises Kakiemon-style porcelain. After reading it, I was happy to have done so.

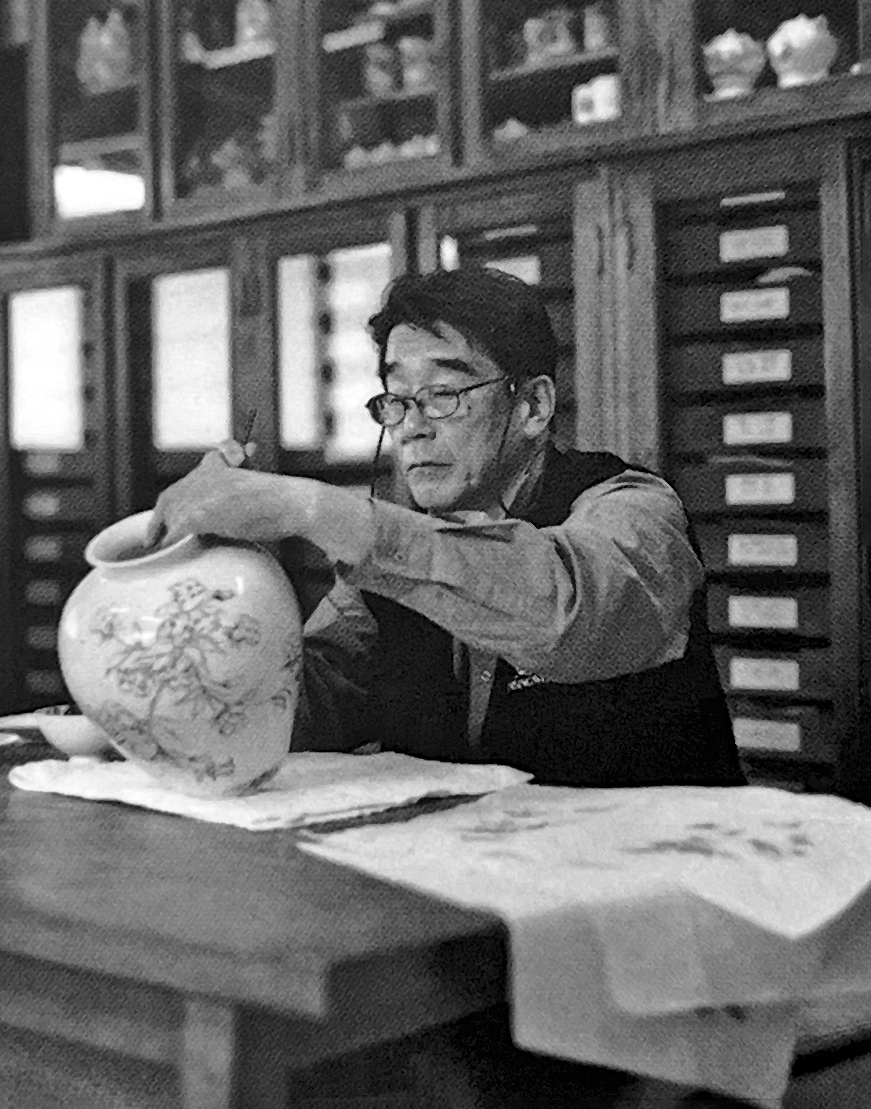

The text of the book is based on an extended series of interviews held over three years with the late Sakaida Kakiemon XIV, who gave up his birth name “Masashi” after his father (the thirteenth Kakiemon) passed away in 1982. It was originally published in Japanese as Yohaku no bi Sakaida Kakiemon in 2004. The English translation was first published in 2019. The Kakiemon name is, of course, renowned the world over and this book not only provides a fascinating insight into the history of the Kakiemon kiln and the techniques and traditions behind the acclaimed porcelain ware, but also into the master craftsman himself.

The establishment of the Kakiemon dynasty of potters came about as a direct result of the Japanese invasions of Korea at the end of the sixteenth century during the Momoyama period, during which highly skilled Korean potters were taken prisoner and taken back to Japan. Here they established kilns and passed on their knowledge to local Japanese potters. One such Korean potter, Yi Sam-Pyeong, settled in the Arita area of modern day Saga Prefecture on the island of Kyushu and is credited with discovering porcelain stone on nearby Mt. Izumiyama, which has been the mainstay of porcelain ceramics from the area ever since. By the mid-seventeenth century, civil war and trade restrictions imposed in China, the largest producer of porcelain in the world, resulted in the cessation of export porcelain. As a substitute the Dutch East India Company turned to Japan and started exporting porcelain from the port of Imari (hence the name of this ware), with the bulk of the work originating from neighbouring Arita (the location of the Kakiemon kiln).

The book is divided into three parts, giving it a nice balance. Part one is autobiographical, in which Kakiemon discusses his childhood, his father and grandfather, but also the origins and background to the Kakiemon name, the responsibilities of running a kiln and what the name, style and traditions mean to him. Part two, Production, provides an insightful overview of all the processes that go into producing Kakiemon porcelain, from the specific clay used, to the whole glazing and firing processes, including detailed diagrams of the two main Kakiemon kilns. He encapsulates perfectly the distinct properties that typify Kakiemon ware: the concept of yohaku or “empty space”, aka-e (polychrome motifs) and the crucial element of nigoshide, a local term that means “water that rice has been washed in” for the milky-white surface that Kakiemon porcelain is famed for. Part three is entitled Appreciation, and takes a close look at characteristics of style, accompanied by fine historical examples in colour.

The fact that the book was compiled from a series of interviews adds to the overall relaxed and informal tone of much of the text. Kakiemon XIV comes across as being a self-effacing, good-humoured character, often joking about incidents and exploits during his upbringing. The autobiographical section is therefore rather anecdotal in nature and written in a style that sometimes needs a little getting used to. The sentences are often short and to the point, but I think the translator has done a fine job in rendering the tone and idiosyncrasies of the author’s native tongue. There are also quite a number of references to people and places that might sound somewhat alien to the English-language reader. But again this is surely a very minor pill to swallow considering the book was originally intended for a Japanese audience. In many ways it can often lead to additional research to help provide an even better understanding of Japanese ceramic culture in general. Moreover, each section includes insightful explanatory notes at the end, which are very helpful.

Ultimately, the book is a very pleasant read and offers something for everyone, particularly ceramicists and ceramic aficionados, but also those interested in Japanese art and culture in general. It is also laden with numerous pearls of wisdom. On the subject of transmission and tradition, for example, he explains that “tradition refers to taking the techniques that have been transmitted to you and adapting them in your own way, developing them…to take the work that has been been developed through the years and turn it into something that contains a contemporary air—surely that is the real meaning of tradition”. And this holds true whether you are Kakiemon XIV working with overglaze enamels and porcelain in Japan, John Dermer with salt-glazed stoneware in Australia or Niek Hoogland with slip-decorated earthenware in the Netherlands. Again: “Creative people are forever searching for something more. It is their fate, and it continues until they die”. And another: ”I think it is true in all handicrafts, particularly ceramics, that impurities have an important role to play. I am not sure how to explain it, but the impurities are what imbue ceramics with ‘character’ or ‘feeling’; I believe they are vital in order to bring out the true flavour of the work”. As to his business and his own role in its success, Kakiemon XIV likens the kiln to an orchestra and himself to the conductor who “serves to coax the musicians to employ their skills to the fullest in order to create perfect, beautiful music”. I could go on and on, but I will leave you to choose your own favourites.

The book closes with a short interview, looking back on the previous three years. The author hopes that it will “serve to transmit my thoughts to those who read it” and that it will “open the door to our world… [and] people will be able to understand our work much better”.

On his death in 2013, Kakiemon XIV was succeeded by his son Kakiemon XV, who wrote the introduction to his father’s book. In it, he explains that it was his father’s dislike of excessive decoration that led to the discovery of “the beauty of emptiness” and the way in which this emptiness enables “a sense of a world to open up within the work”. This book has certainly helped open up the world of Kakiemon porcelain ceramics and is a splendid addition to the field.

Kakiemon XIV was born in 1934 and passed away in 2013. He was designated a Living National Treasure by the Japanese government in 2001.

Neale Williams

. . . . . . . . .

The Art of Emptiness by Sakaida Kakiemon XIV (translated by Gavin Frew)

(Originally published in Japanese as Yohaku no bi Sakaida Kakiemon by SHUEISHA, Inc. in 2004)

Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture (JPIC)

210 x 148 mm

208 pages

ISBN: 978-4-86658-063-0

. . . . . . . . .