Radical Clay

. . . . . . . . .

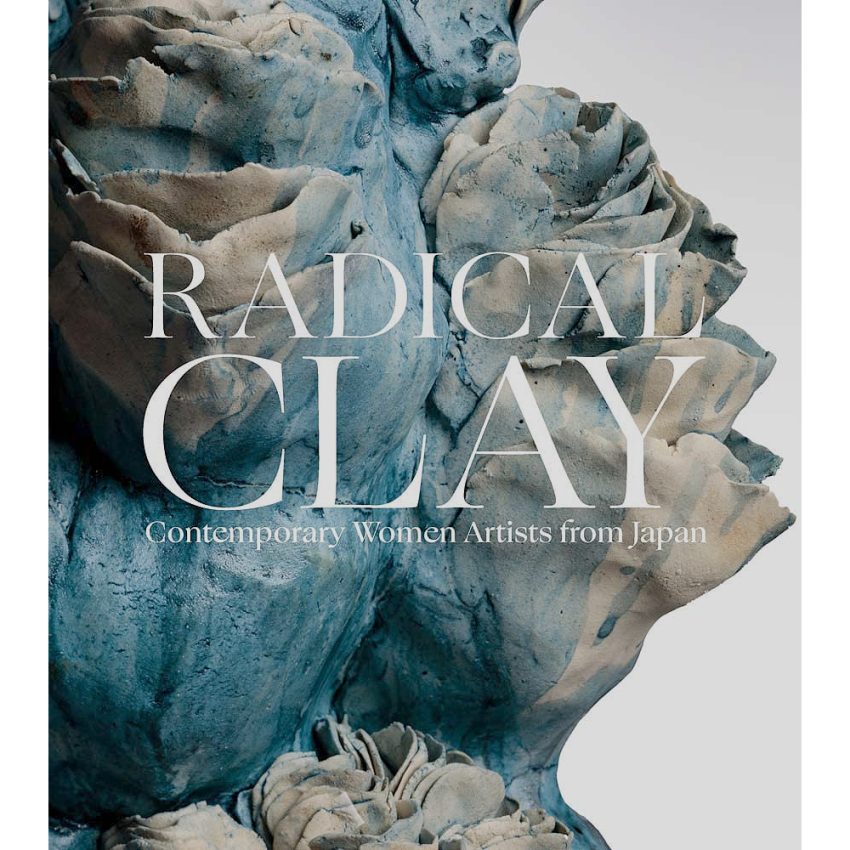

Radical Clay: Contemporary Women Artists from Japan edited by Joe Earle, with essays by Joe Earle, Janice Katz and Hollis Goodall

Before doing research into her insightful book Women Potters: Transforming Traditions, Moira Vencentelli questioned why, as a trained art historian, she had not known that in the majority of traditional, rural societies pottery was a female task. On consideration, she says that her perceptions of the world of ceramics, indeed of art in general, had been based on her Western experience and that, because knowledge is never innocent or disinterested, it is always grounded in an individual or particular world view. This is a truism that not only speaks volumes about our inherited value systems but also brings to light our often flawed preconceptions and cultural chauvinism.

This sense of prejudice is highlighted by Joe Earle in his introductory essay to Radical Clay: Contemporary Women Artists from Japan: “Just as in other cultures…women’s contributions to artistic creativity have gone largely unrecognised until very recently”. Indeed, when it comes to the Japanese archipelago – one of the oldest centres of ceramic production in the world – archaeologists now assert that the ornately impressed decoration on Jōmon era (c. 10,500 to c. 300 BCE) earthenware would not have been possible without the participation of women. Earle argues that it was not until the introduction of newer technologies around the fifth century CE, such as the potter’s wheel and higher-temperature firing methods, which involved “greater physical strength”, that Japanese men increasingly played “a more dominant role in ceramic production”. Whether this was the actual reason for any such transition in the production process is an intriguing subject in itself and very much open to debate. Nevertheless, the author does go on to reference Louise Allison Cort (Women in the Realm of Clay) to point out that “evidence suggests that, for the most part, Japanese women might have carried heavy loads of clay, kneaded it in preparation for throwing, spun wheels for men, but they were strictly excluded from the key creative processes”, thereby concurring that it was not simply a matter of physicality, but there were also other entrenched social factors at play.

And this would remain the status quo until the nineteenth-century when the Buddhist nun and poet, Ōtagaki Rengetsu, created a name for herself with her extremely popular stoneware vessels incised with her own poetry. But it would still take many more decades, well into the post-war era, before such ingrained social attitudes would finally start to change, albeit “in the face of opposition from male teachers and senior potters”.

Radical Clay: Contemporary Women Artists from Japan “celebrates the originality and virtuosity of thirty-six women ceramicists from Japan, as represented by selections from the private collection of Carol and Jeffrey Horvitz”. The book is published by The Art Institute of Chicago to coincide with various exhibitions in the United States from December 2023 to August 2025. And although it can easily stand alone as a work to be enjoyed in itself, its whole look and feel does not hide the fact that it also serves as a quality exhibition catalogue. It is nicely edited by Joe Earle, who has a strong background in Japanese art and culture, and includes insightful essays by Earle and curators of Japanese art, Janice Katz and Hollis Goodall.

The range of ceramicists represented is impressive. And yet there is a nice flow to the selected artists from beginning to end. The majority of the ceramicists featured in this volume are graduates from art schools and are therefore representative of predominantly contemporary aesthetics that explore present-day issues in sculptural form. Of course it is also a generational attribute. The older ceramicists grew up in a very different environment and faced social and artistic constraints that are completely archaic and passé in today’s society. And with the rise of an art-school educated generation, with a greater freedom to focus on finding a voice to more personal, social and artistic concerns, it is hardly surprising that younger ceramicists have turned to developing novel and innovative themes. That said, it is not necessarily a rejection of the traditional wheel-thrown vessel forms we are all familiar with from Japan (although this could play a role), as many of these ceramicists continue to use such forms as a basis for their artistic voice.

These representatives include Tsuji Kyō (1930-2008), who was committed to working with traditional ceramic materials and techniques and who suffered “unthinkable feudalistic sexist prejudice” throughout her career and led her to dropping the customary female suffix ko from her personal name; Tokuda Yasokichi IV (born 1961), who took over the family kiln from her famous father (Living National Treasure Yasokichi III) in 2009; and Fukumoto Fuku (born 1973).

Taking inspiration from the female body, Tsuboi Asuka (born 1932) spearheaded the Joryū Tōgei group (Women’s Association of Ceramic Art), which although sharing a similar philosophy, formed a counterweight to the male-dominated Sōdeisha group. And female sensuality and sexuality is also found in the expressive forms of Futamura Yoshimi (born 1959), although her wonderfully textured work also has close associations with the natural environment.

Koike Shōko (born 1943), in particular, was “among the first Japanese female ceramic artists of the post-war period to make the evocation of natural and geological forms…a cornerstone of her practice”. While others include Hiruma Kazuyo (born 1947), whose signature sekisō (laminar) technique involves stretching thin layers of clay to create sedimented geological strata in her vessels; Ogawa Machiko (born 1946) and Inaba Chikako (born 1974), whose soft fluted swirls show an affinity with the fluid forms made by Fujikasa Sakoto (born 1980); Konno Tomoko (born 1967) who creates otherworldly organic forms; and Shingū Sayaka (born 1979) with her subdued and sombre flower heads.

The more recent generation of ceramicists includes work that will “appeal to a younger taste that finds beauty in the sexual, uncanny, and weird”, including the sinuous, pulsating forms of Mori Aya (born 1989) and the biomorphic, masochistic sculptures of Kawaura Saki (born 1987). Others demonstrate a modern eclecticism and a typical ability “to assimilate disparate elements from the outside world and form them into something unmistakably Japanese”, such as Ōishi Sayaka (born 1980) and Tomita Mikiko (born 1972), who became fascinated by the Moorish decorations she saw as a child growing up in Portugal and the organic images she found in her father’s science magazines.

Particular attention is paid to Mishima Kimiyo (born 1932), who focuses on the “horrors of urban centres and their disgorgement of garbage” and whose work is “both trash as art and art as trash”. Hollis Goodall has written an extremely perceptive essay on this singular artist and is well worth the read.

Radical Clay: Contemporary Women Artists from Japan provides a perfect introduction to the work of contemporary women ceramic artists from Japan and insight into the specific themes that relate to them and the hurdles they have faced and have had to overcome. Radical Clay is a catchy title but might seem somewhat of a misnomer to many readers. From the context of how gender has played a role in the development of post-war ceramics in Japan, it is quite understandable and should be applauded. Beyond such local cultural constraints, however, focus on gender-specificity in contemporary ceramics is rather a moot issue and can easily become a limiting factor. It says nothing about radical progressiveness in general and very little about the majority of work being produced today. Moira Vencentelli astutely pointed out that “value is not intrinsic to objects but is assigned to them by people”. We should therefore continue to look forward and celebrate the inspirational work that ceramic artists of all genders and all persuasions are making now and in the future.

Neale Williams

. . . . . . . . .

Radical Clay: Contemporary Women Artists from Japan edited by Joe Earle, with essays by Earle, Janice Katz and Hollis Goodall

Art Institute of Chicago

287 x 253 mm

128 pages (illustrated throughout)

ISBN: 978-0-300-27323-6

. . . . . . . . .