Bartmann Jugs

. . . . . . . . .

Baardmannkruiken/Bartmann Jugs/Bartmannkrüge: Stoneware 1200-1950 by Sebastian Ostkamp and Wil Snip, with contributions from Jos Koldeweij and Ralph Mennicken

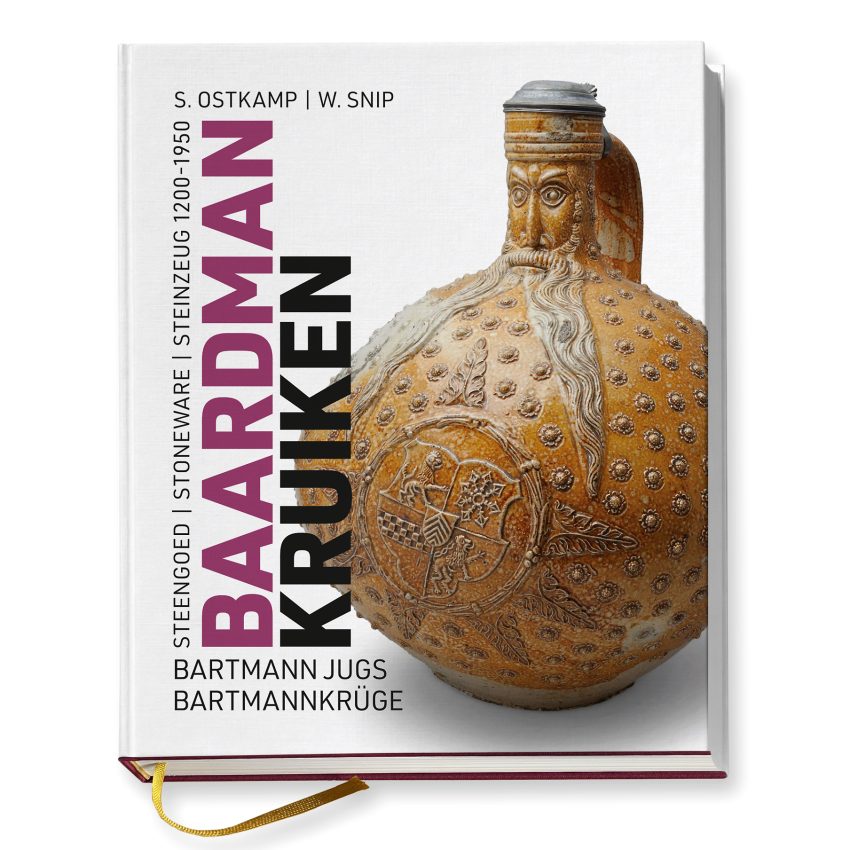

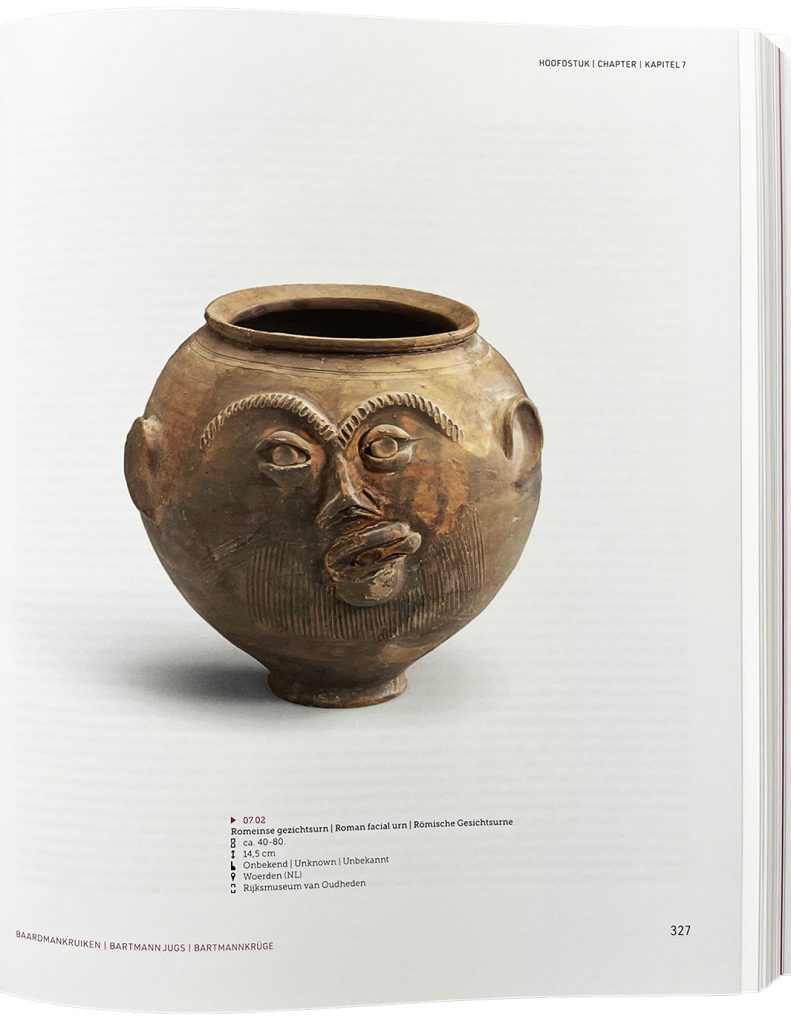

Scowling, grimacing and belligerent, but also jovial, genial and benevolent: who has not been intrigued by these plump-bellied stoneware vessels with strange bearded men adorning their necks? Anthropomorphic characters have been represented on pottery since time immemorial, often in a ritualistic context, but also for purely decorative purposes. Understanding the precise origins of Bartmann jugs and the significance of their iconography, if that exists, has long since occupied cultural historians, both amateur and scholarly alike, usually in the form of learned articles or exhibition brochures. It is therefore exciting to see the publication of a new major work that provides an extensive look at all aspects of this fascinating genre.

This handsome cloth-bound book with a ribbon marker and printed on high-quality glossy paper is advertised as a coffee-table book for reading and browsing. Given its formidable size and weight, that probably sums it up well. The two main authors, Sebastian Ostkamp and Wil Snip, both have a background in archaeology and Ostkamp in particular has published widely on the subject of medieval stoneware. The book is trilingual and is written in adjacent columns in Dutch, English and German. It therefore caters to a wide audience, especially enthusiasts with a particular interest in the history of Rhineland stoneware pottery. That said, it is clear that the original text has not only been written in Dutch and translated into English and German, but that the content (especially in the first few chapters) is also broadly directed at a Dutch readership. In itself this is not so surprising, seeing that the book’s origin stems from an article on Bartmann jugs the authors wrote in the Dutch-language magazine Vind in 2018, which appealed to its readers to submit photos of their favourite bearded men jugs. The authors were so inundated with responses that they decided it could form the basis of this current work. It has resulted in an impressive 656-page volume containing more than 1,400 images and illustrations.

The introduction is written by Jos Koldeweij, professor emeritus of Art History of the Middle Ages, and is enlightening and a very interesting read. It examines the evolution of such vessels and how Bartmann jugs were used in various ritualistic contexts, such as “witch bottles”.

“All witch-Bartmann jugs found closed, of which the contents were examined, were found to contain urine.”

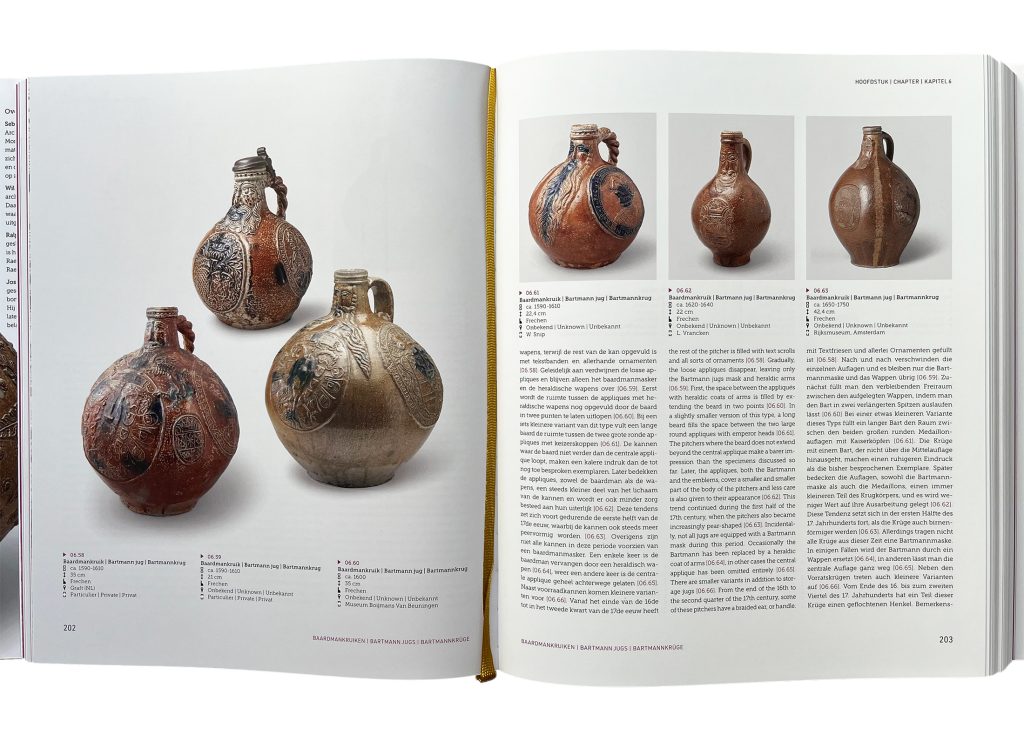

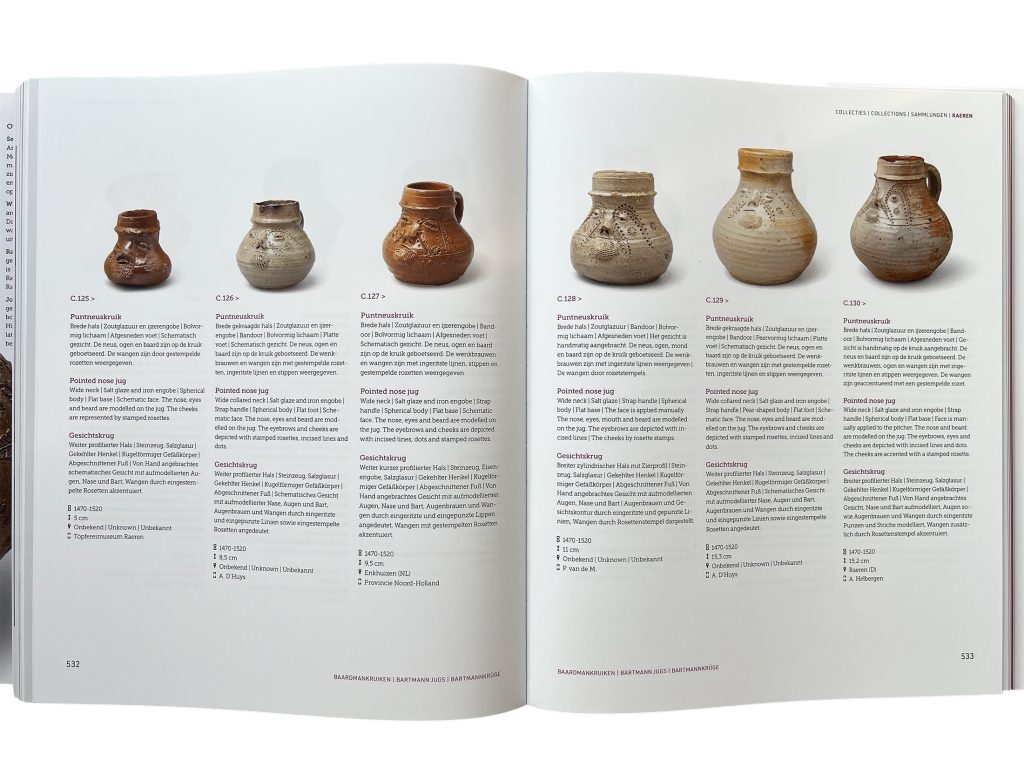

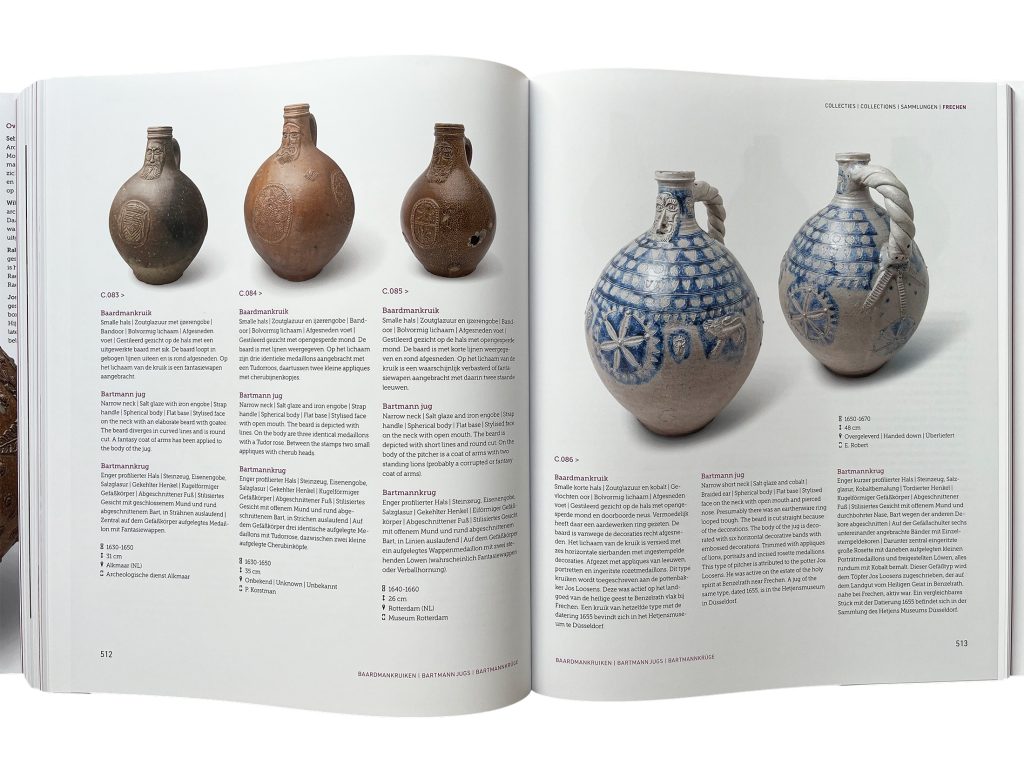

The first two chapters discuss past Dutch collectors of such stoneware and historical finds in the Netherlands and environs. Chapter three is a short historical essay about the region and the development of urbanised society as an important factor for demand and trade. This leads into the main body of the work and traces the history of Bartmann jugs (human heads and faces have been represented on pottery since classical antiquity) and how they developed from anthropomorphic representations, through the elaborate pointed nose vessels of the 15th and early 16th centuries into the more identifiable forms of the typical bearded men examples from the late 15th to 18th centuries that we are familiar with today, right up to the rather gaudy imitations of the 19th and 20th centuries. These chapters provide ample space (more than 230 pages) to discuss how stoneware ceramics developed in the Rhineland area and the major centres of production, including Frechen, Raeren, Cologne, Siegburg, Westerwald and Langerwehe, as well as pointing out subtle variations and influences. It makes for a thoroughly interesting read throughout and is accompanied by excellent images. These chapters alone greatly extend the book’s appeal to a more international readership.

There then follows an in-depth analysis of the symbolism behind pointed nose and bearded men vessels as well as themes, both religious and profane, and possible connotations. Although the commentary is enlightening and thorough, it does make a number of direct associations that at times seem somewhat tenuous rather than definitive. But as is often the case with such historical material, it is practically impossible to know anything with complete certainty. In this sense, the iconography of anthropomorphic motifs on such vessels and their meanings does require a measure of interpretational conjecture. Clearly, both religious and secular themes play a significant role, such as the admonishing moralistic messages indicating the dangers of gluttony and revelry, as well as the symbolic links to older, more “paganistic” traditions, as is the case with the representation of the Green Man and its culture of protectionism and apotropaic rituals. The chapter provides an insightful review of many such possible influences. One thing is certain, however, is that it is easy to forget how quickly certain motifs and tastes can become integrated into our social life, become embedded in our working practices and passed down until they lose their original context. As the author rightly points out, “religious significance of the Bartmann masks would have been completely lost towards the end of the 16th century, to become purely decorative, as an offshoot of a tradition.”

The final extensive chapter in the book contains an impressive 220-page overview of examples held in both private and public collections and produced in the major ceramic centres, all with well-captioned, high-quality photos. Something you can return to time and again.

As pointed out, the book is published in the Netherlands and has been translated into English and German. For German readers, there is little doubt that the German translation is completely in order as it was carried out by Ralph Mennicken, descendent of the famous Mennicken pottery family in Raeren, Belgium, and director of the eponymous Pottery Museum in this historic pottery centre. It would have been impossible to find a more suitably qualified contributor.

The English translation, however, does suffer from quite a few hiccups. Not only is it strewn with typical “Dutchisms”, there is also an overabundance of inconsistencies and poor or incorrect word choice. This is a bit of a shame and can be a little distracting at times. It often forces you to read between the lines or to glance sideways to the Dutch and German texts to understand the context of the translation. A “verlopen zuiplap”, for example, is not an “expired” drunkard (whatever that may be) but rather “bedraggled” or “dishevelled”; a “steengoedbakker” is not a stoneware “baker”, but a stoneware “potter” (as correctly translated into German as “Steinzeugtöpfer”); and “potaarde” is not “potting soil” (for the geraniums?), but “potting clay”. And this inconsistency is also reflected in the use of certain names, such as Robert “Bellarmijn” in English and the claim of him being an “English cleric”. Of course, this figure refers to the famous Italian cardinal, Roberto Bellarmino, known in English as Robert “Bellarmine”, who was ridiculed for his strict anti-alcohol stance and for his role in the Counter-Reformation in North-West Europe. (These vessels are also commonly known as Bellarmine jugs.) Such minor linguistic drawbacks can be found throughout the book and it would have been nice to see the same degree of expertise and attention to detail at the editing stage for the English text, preferably by a native speaker with better knowledge of the subject area. As it stands, it could give a somewhat distorted historical perspective to the unassuming English reader. In general, though, it should be said that the English translation does greatly enhance the book’s appeal and enables its subject matter to be enjoyed by a much broader audience. And for that reason alone, it must be commended.

In conclusion, this is a finely produced work, accompanied by quality photography and thought-provoking essays. It is not intended to be an academic work and certainly does not read as such. It will therefore be of interest to almost everyone interested in the history of pottery, but especially in how stoneware has evolved in North-West Europe and the particular appeal of Bartmann jugs. If you have not already visited the wonderful pottery museums in the area, from Raeren in East Belgium, to Langerwehe, Frechen, Siegburg and Höhr-Grenzhausen in Germany, this book will surely inspire you to do so. Highly recommended!

Neale Williams

. . . . . . . . .

Baardmannkruiken/Bartmann Jugs/Bartmannkrüge by Sebastian Ostkamp and Wil Snip, with contributions from Jos Koldeweij and Ralph Mennicken

Uitgeverij PolderVondsten

656 pages, approx. 1,400 illus.

ISBN: 978-90-817063-9-1

. . . . . . . . .